The idea of the fourth dimension, commonly referred to as the “other dimension,” or the one dimension of time and space that no one had been able to confirm or explain, captivated mathematician Charles Howard Hinton as much as it irritated him. Einstein made an attempt. In his Theory of Special Relativity, Einstein concluded that “time is inseparable from space” and that “time is the fourth dimension.” Since that time, science fiction authors have employed the space-time continuum in their novels to great dramatic effect.

Hinton, though, was the author of the seminal piece on the subject, which was published in 1884, when Einstein was only a young child. “What is the Fourth Dimension?” asks. There is no physical evidence for the existence of a fourth dimension, according to Hinton.

He implied that this was a problem: “If we think of a man as existing in four dimensions, it is hard to prevent ourselves from conceiving him prolonged in an already known dimension.” Hinton illustrated how one can only reach three dimensions by using a four-cornered room, or cube, as an illustration. He acknowledged that “space as we know it is subject to limitation.”

Hinton, though, constructed a three-dimensional bamboo dome with uniformly spaced geometric designs to instruct his kids in math. Sebastian, his son, recalled ascending and dangling from the dome as their father pointed out junctions for the kids to recognize.

“X2, Y4, Z3, Go!” Hinton would yell out to the kids.

Hinton died unexpectedly in 1907 from a cerebral hemorrhage and while he is mostly remembered for his work on the fourth dimension, in stark contrast, he is also credited with introducing the first pitching machine – more like a gun – called the “mechanical pitcher,” and designed for the Princeton University baseball team. The machine used gunpowder to fire the ball.

But the geometric dome he created for his children also had a lasting effect. Especially on his youngest son Sebastian. Shortly after getting married, he had three kids and his wife was a kindergarten teacher at a near by school in Chicago.

His wife was determined to create learning environments for her school children and others that would be joyfully experimental. In 1920, while watching his wife’s school children playing outside their Winnetka, Illinois home, Sebastian had a revelation. Why not build something they could climb on?

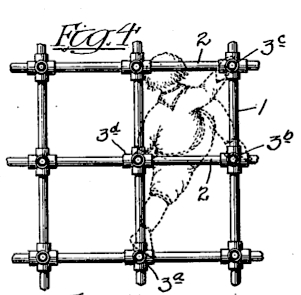

He envisioned a three-dimensional structure similar to his father’s geometric dome, but for play rather than instruction. He reportedly jotted down the idea on a napkin and perfected the plan for a patent submission. Then he built it. Hinton called it a Jungle Gym.

At the time of its conception, the Jungle Gym was never heralded as the important contribution to the children’s playground as it is today. Hinton’s only recorded words about his invention are attributed to his detailed patent filings: “Children seem to like to climb through the structure and swing their head downward by the knees, calling back and forth to each other. A trick which can only be explained of course by a monkey’s instinct.” While the name Jungle Gym never officially changed, many people began seeing the correlation with the primate’s distinctive behavior and started calling it “monkey bars” instead.

Tragically, just a few years after creating the Jungle Gym, he committed suicide in a clinic after reportedly being treated for depression. Hinton’s original Jungle Gym is permanently on display in the backyard of the Winnetka Historical Society Museum.